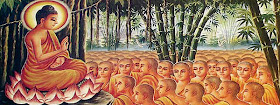

Wisdom Quarterly based on Tipitaka.net ("Fruits of Recluseship," Samannaphala Sutta, DN 2)

WHAT

The discourse on the Fruits of Recluseship is the second sutra in the Long Discourses of the Buddha. It gives the background to the fraticidal King Ajatasattu, who became a lay

disciple of the Buddha like his father but a little too late.

|

| Monks, Chiang Mai (HipRoad/flickr.com) |

It starts with Ajatasattu in his palace seeking advice from

his ministers which wandering ascetic or Brahmin he should visit. Ignoring recommendations

from six ministers, the king turned to Jivaka Komarabhacca for

advice.

Komarabhacca informed Ajatasattu that the Buddha was staying at his mango grove and

suggested making a trip there. Ajatasattu set out on

his royal mount to meet the Buddha, together with Komarabhacca, and a large number of

women on elephants, and a procession of torch-bearing attendants.

Later it is revealed that the king had previously spoken to the

six recommended ascetics but was not pleased with their teachings.

According to

the Buddha, King Ajatasattu would have become a stream-winner if not for the hienous

crime of killing his father.

WHERE

At Komarabhacca's mango grove in Rajagaha, the capital city of Magadha

At Komarabhacca's mango grove in Rajagaha, the capital city of Magadha

WHEN

On the full moon night of Komudi in the month of Kattika, after Ajatasattu had already usurped his father King Bimbisara as the ruler of Magadha.

On the full moon night of Komudi in the month of Kattika, after Ajatasattu had already usurped his father King Bimbisara as the ruler of Magadha.

WHO

The main dialogue is between the Buddha and Ajatasattu. Other personalities mentioned are Queen Vedehi, Prince Udayibhadda, and the six famous ascetics of the Buddha's time.

The main dialogue is between the Buddha and Ajatasattu. Other personalities mentioned are Queen Vedehi, Prince Udayibhadda, and the six famous ascetics of the Buddha's time.

- King Ajatasattu is the son of Queen Vedehi.

- Prince Udayibhadda is Ajatasattu's newborn son.

- Aggivessana is the family name of Nigantha Nataputta called "Mahavira" (Great Hero), the historical founder of Jainism.

The Six Ascetics

The six contemporaries mentioned are considered representatives of various Indian philosophical movements of the time. They are: Purana Kassapa,

Makkhali Gosala (originally Mahavira's student), Ajita Kesakambala, Pakudha Kaccayana, Sancaya Belatthaputta, and

Nigantha Nataputta (literally, the "Possessionless-One, Son of Nata," Mahavira).

The sutra opens a window into their individual teachings,

as reported by King Ajatasattu to the Buddha.

Unfortunately, each of these accounts is very brief.

The sutra opens a window into their individual teachings,

as reported by King Ajatasattu to the Buddha.

Unfortunately, each of these accounts is very brief.

Not all who wander are lost.

Respect for Wanderers

This sutra reveals a culture that respected truth seekers who were wandering ascetics (shramanas), that is, spiritual wayfarers. They were an alternative to conventional Brahmin temple priests who held the Vedas as their sacred texts and ultimate authority, much as St. Issa (Jesus) wandered rather than being involved with the temple hierarchy and unquestionable sacred texts like the Talmud (part of Judaism's Bible).

|

| The Buddha's India, the Middle Country |

King Ajatasattu, who usurped his powerful father King Bimbisara's position to become the ruler of the most influential area (Magadha) in India at the time, expressed his respect for any recluse, even if the person used to

be his servant.

WOMEN

Until the Buddha accepted women into his Monastic Order, all female recluses were Jains, since Mahavira had earlier accepted women. Buddhism became the first world religion to elevate women to equal spiritual status and social standing (at least within the Sangha). Jainism never caught on outside of India. However, the sexual equality the Buddha established was eventually subverted: Additional rules (garudhammas) were instituted and backdated as if the Buddha had always intended to subordinate women, which does not make historical sense as explained by Ven. Tathaloka.

The Fruits of Recluseship

|

| Novice meditating, Burma (Dvlazar/flickr.com) |

Basic rewards

When asked about the fruits of Buddhist recluseship, the Buddha explained to these to the

king:

- respect, protection, and provisions from the king and lay people. These were benefits even other wandering ascetics could expect in ancient India with its charitable dana system -- reciprocal benefits of spiritual seekers aided and in turn aiding the people and society.

- endowment with morality as explained in the "The Net of All-Embracing Views" or Brahmajala Sutra.

- guarded sense faculties (indriya samvara)

- mindfulness and clear comprehension (sati-sampajana)

- contentment (santosa).

Intermediate rewards

Detached from the Five Hindrances, greater benefits arise from the

successful practice of meditation:

- the four material absorptions (jhanas)

- insight-knowledge (vipassana nyana)

- advanced spiritual capabilities

Highest rewards

The highest rewards, the ultimate goals of the Buddhist path, is the

complete realization of the Four Noble Truths and liberation from samsara -- rebirth and suffering.

No comments:

Post a Comment