Martin MacInnes (ScienceAlert via MSN, 2/28/24); Douglas Adams; Euglenoids, Dhr. Seven, Sheldon S., Pat Macpherson (eds.), Wisdom Quarterly COMMENTARY

|

| When we first arrived, it was vegan Eden. Tasty! |

(Or, to put it another way, we fall halfway between nothing and everything.) [Or, to put it yet another way, this is a middle world between heaven and heck, between glory and oblivion, light and shadow, the deva worlds and hellish narakas.]

|

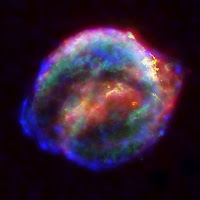

| Life arrived on Earth. It did not begin here. |

Whether or not this claim is strictly true, it’s arresting and resonant in all sorts of ways. [To think that the only difference between the two destinations is karma is hard to accept, but the Buddha was a Karmavadin, a "Teacher of Karma," for just that reason; it's not obvious, and it needs to be known.]

Each of our lives might feel like a whole universe – surpassingly important and infinite in scope – and yet from another perspective, each is utterly trivial and ephemeral.

- It's almost as if Douglas Adams, writer of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (radio series), was exactly right in suggesting that the worst thing that could possibly happen to someone is being put in the TOTAL PERSPECTIVE VORTEX:

It’s an impossible paradox, this state of having both a surplus and redundancy of value, and it brings with it certain creative and moral opportunities.

I’m interested in how these opportunities might be explored in fiction, how scale can defamiliarize human life, and indeed all life, reminding us of the infinitesimal nature of its expanse and the improbability and wonder of its existence.

In each of my novels, and especially In Ascension, I have placed non-intuitive spatial and temporal perspectives next to the more mundane concerns of my characters.

Telescopes and microscopes recur, as do deep time, evolution, and the life cycles of parasites and viruses.

Alongside this, characters are eating, walking between rooms, anxiously going over circular thoughts, worried about their families, or bored.

The lens zooms in and out from “domestic” to “alien” scenes. I’m not doing this to mock or belittle my characters, but rather to try to evoke something of that paradoxical quality in which we are both infinite and infinitesimal, equally close to something very large and very small.

I’ve always been drawn to fiction that attempts this. When scenes with very different perspectives collide, the effect can be startling, exhilarating, unforgettable.

|

| Who's afraid of V. Woolf? |

In the following part, “Time Passes,” the perspective undergoes a radical shift. The house is empty, the people long gone; Mrs. Ramsay, we are informed in two short lines enclosed between brackets, like an afterthought, is dead.

I will never forget the shock and thrill of first reading this. I didn't realize fiction could do this; Woolf’s audacity and ambition took my breath away.

She had shown, tragically, the power and precarity of every consciousness. It’s a truism that cannot be repeated enough: Life feels infinite, and it’s gone in a second.

Much of Woolf’s fiction is interested in this dissonance, and it is not coincidental that, as well as experiencing both world wars, she lived through radical advances in telescopic power that changed all understanding of the size of the universe.

And it should be no surprise – though it apparently still is to many people – that Woolf was not just an avid reader of astronomy books and science fiction, but saw herself engaged in a lifelong project of writing that bore comparison to the most ambitious works of sci-fi.

|

| In Ascension (Martin MacInnes, Freya Miller) |

The protagonist of In Ascension, Leigh Hasenbosch, is a microbiologist who travels into deep space. She experiences not only astonishment at seeing the whole Earth, but dejection at seeing the planet disappear.

Anthropocentrism -- unarguably the default perspective in English language fiction -- has never looked so absurd. [That is the idea that Earthling humans are the center or some significant part of the universe.]

Approaching the Oort cloud, she is aware of the other orders of life around her, from algal food stocks to the colonies of bacteria travelling between her and the other crew.

Beyond the composite walls of the ship, there is nothing. Since childhood, after an epiphany while almost drowning, Leigh has pursued the origins of life, absorbed by the theory of symbiogenesis and struck by its improbability.

|

| Look inside 13K animals, no scalpel needed |

Her life and work gather around this ambiguous pursuit of origins. Which scale, then, is “correct”? Which story is she really invested in -- the universal or the personal?

The answer, of course, is both. For neither answer alone can be sufficient.

Martin MacInnes’s In Ascension, published by Atlantic Books, is the latest pick for the New Scientist Book Club. Sign up and read along HERE.

.

[Don't like nerds who take their sci-fi seriously? Read The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy instead. It's perhaps the greatest comedy ever written -- relevant, important, brilliant, genius, tackling the big questions in life. It's a Wisdom Quarterly top pick.]

Wha's "life"? New form neither plant nor animal

No comments:

Post a Comment