Samaneris (novice nuns) circumabulating Shwedagon Pagoda, Rangoon, Burma (AFP).

The bestowing of full ordination for women -- which lapsed centuries ago with no easy way to restore it or, as some argue, with no legitimate way to restore it at all -- is revolutionary. However, women were reinstated a few years ago in India using senior Mahayana nuns as preceptors, through the brave work of some monks from Sri Lanka. (Currently, it is possible to ordain in the US as a higher ordination nun at West Virginia's Bhavana Society, pictured, under the auspices of the Sri Lankan abbot Ven. Gunaratana, "Bhante G").

Novices on their way to full ordination as Theravada nuns through the Bhavana Society of West Virginia (bhavanasociety.org) But Ajahn Brahm's actions is sure to help legitimize female ordination. It has even been argued that the rules banning women from higher ordination after the lapse of the Bhikkhuni Order was due to rules invented by men or monks, not by an actual decree or set of eight special rules binding only on women laid out by the Buddha.

The Theravada lineage is the oldest extant Buddhist tradition. It maintains the disciplinary regulations (Vinaya) that facilitate the survival of the Sangha and extend the duration during which the Dharma exists in the world. The rules laid out by the Buddha are only altered during formal councils, of which there have been very few in the past 25 centuries. But part of the problem as to whether any rule can be altered at all falls at the feet of Ananda (and perhaps Mara). The Buddha is reputed to have said that after his passing, the Sangha could gather and change the minor rules but not the major rules. Ananda had a momentary lapse. So affected was he by the news of the Buddha's impending demise (parinirvana), that he failed to asked the Buddha which were which.

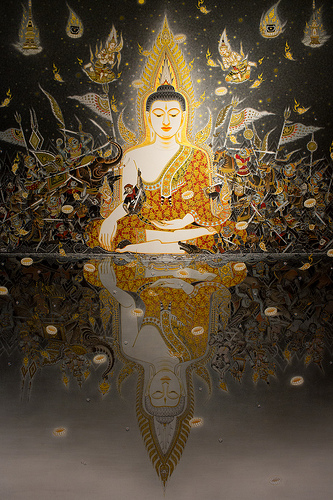

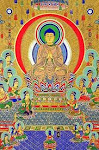

The Buddha conferring ordination to the first Buddhist nun, his mother, Maha Pajapati

The Buddha conferring ordination to the first Buddhist nun, his mother, Maha Pajapati

The controversy sparked by female ordination in the first place, a momentous decision for a world religion, is dwarfed by the controversy to re-establish the practice after it lapsed. Some Buddhist countries, like Thailand, never had a Bhikkhuni Sangha (Buddhist Order of Nuns). Ajahn Brahm, although a Westerner and the abbot of a monastery and (lower ordination) nunnery in Australia, was ordained in the Thai tradition. This makes his actions quite radical, and one can imagine that it is not a popular move among very pious Thai Buddhists afraid to deviate in any way from orthodoxy.

Nevertheless, Thailand is quite progressive, particularly with regard to gender and sexual politics. (Thailand, after all, has a third gender, the kathoey). One prominent university professor decided she wanted to be recognized as a fully ordained Buddhist nun (a bhikkhuni rather than a "novice" or 10 precept samaneri). And this caused quite a stir in Thai society, where monks enjoy a particularly prominent status and wield tremendous influence. Individual monks of course do not have much say, but the Sangha does. It is an integral part of society. The "Sangha" is represented, then, not by ordinary monks but by abbots and long standing elders (theras) who have quite a bit of say in secular matters.

This entire episode is quite sad. For other Buddhist traditions -- Chinese Mahayana, Tibetan Vajrayana, and independent Western movements -- have longstanding Bhikkhuni Orders. And those nuns have only helped the tradition as a whole. Theravada has always had 10 Precept Nuns, who look and act like fully ordained monastics. Their status is already subordinated to that of men because of the eight special rules (of dubious origin) for women. So it is not clear what would be lost by their ordination. But what there is to gain is clear -- the dispensation (sasana) would be complete. Women would fully participate in society. The Sangha would be strengthened and enlarged. Women would have the same opportunity to gain enlightenment and enjoy the full support of society. Fear and sexism have kept this from happening for long enough.