Bhikkhu Bodhi, "Arahants, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas"; Dhr. Seven (ed.), Wisdom Quarterly

Competing Buddhist Ideals

|

| Enlightened disciple Ven. Sariputra |

This assumption is not entirely correct, because the earlier Theravāda

tradition has absorbed the bodhisattva ideal into its framework and

therefore recognizes the validity of both arahantship and buddhahood as

objects of spiritual aspiration.

|

| Kwan Yin (Avalokitateshvara) Bodhisattva |

It is important to recognize that these ideals, as they have come

down to us, originate from different bodies of literature, stemming

from different periods in the historical development of Buddhism.

If

we don’t take this fact into account and simply compare these two

ideals as described in Buddhist canonical texts, we might assume that

the two were originally expounded by the historical Buddha.

And we might then suppose that the Buddha — living and teaching in

the Ganges plain in the 5th century B.C.E. — offered his followers a

choice between them, as if to say:

“This is the arahant ideal, which

has such and such features, and that is the bodhisattva ideal, which

has such and such features. Choose whichever one you like” [2].

The

Mahāyāna sūtras, such as the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra (the Great Perfection of Wisdom Discourse) and the

Saddharmapuṇḍarīka Sūtra (the Lotus Sūtra), give the impression

that the Buddha did teach both ideals.

Such "sūtras," however,

certainly are not ancient [but are more recent inventions]. To the contrary, they are relatively late

attempts to schematize the different types of Buddhist practice that

had evolved over a period of roughly 400 years after the

Buddha’s final nirvāna.

The oldest Buddhist texts — the Pāli Nikāyas and their

counterparts from other early schools (preserved most fully in the

Chinese Āgamas) — depict the ideal for the Buddhist disciple as the

arahant (fully enlightened person).

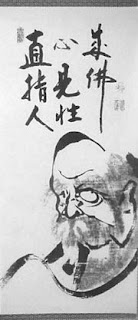

|

| Zen is Japanese Mahayana |

Now some people argue that

because the arahant is the ideal of Early Buddhism, while the

bodhisattva is the ideal of later Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Mahāyāna

must be a more advanced or highly developed type of Buddhism, a

more ultimate teaching compared to the simpler, more fundamental (basic) teaching

of the historical Nikāyas.

That is indeed an attitude common among

Mahāyānists, which I will call “Mahāyāna elitism.”

There is an

opposing attitude common among conservative advocates of the

Nikāyas, an attitude that I will call “Nikāya purism,” which rejects all

later developments in the history of Buddhist thought as deviation

and distortion, a fall away from the pristine “purity” of the ancient

teaching.

Taking the arahant ideal alone as valid, Nikāya purists

reject the bodhisattva ideal, sometimes forcefully. More

No comments:

Post a Comment